The aptly named Zapruder Films operates out of a house just off the trendy Queen Street West in Toronto. With Criterion movie posters plastered on just about every square inch of wall space, shelves of DVDs arranged chronologically, and a Nintendo 64 in the living room, it feels more like a film student’s dorm room than a production house. While some of the staff do live there, nearly a dozen full-time creatives also work from the house, contributing to some of the most interesting and exciting films coming out of today’s independent film scene.

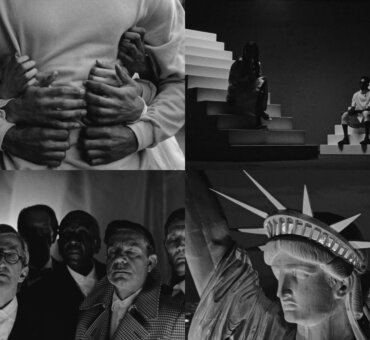

Led by actor, writer, director Matt Johnson, the team at Zapruder first courted controversy in 2013 with The Dirties, a found footage film that boldly tackled a high school shooting narrative and managed to pull it off with an uncanny interplay of light and dark. Their newest film, Operation Avalanche, is once again using the found footage concept, but for a very different story. This time, Johnson and his Dirties counterpart, Owen Williams, play young CIA agents/ cinephiles who pose as part of a documentary crew to try to uncover a Russian mole working inside NASA during the space race of the 1960s. But when they accidentally learn that NASA can’t actually land a spacecraft on the moon, they take it upon themselves to fake it.

In addition to being a suspenseful action flick with plenty of laughs, Operation Avalancheis an homage to film and the process of making movies, from documentaries to science fiction. While the film’s characters demonstrate some filmmaking methods from the days of yore, the Zapruder team had to develop some new techniques to make it look like Operation Avalanche was shot on 16mm and then buried for 50 years.

Cinematographers Jared Raab and Andy Appelle (who play the cameramen in the film as well), and film editor Curt Lobb recently shared some secrets with us about how they seamlessly blended original footage with archival, creating a look for Operation Avalanchethat sold the period — and on a relatively small budget too.

Did you ever look into shooting Operation Avalanche entirely on 16mm?

Jared Raab: We guessed we’d have about 200 hours of shooting. And when we priced it out for 16mm, it would have cost over a million dollars.

Andy Appelle: It just wasn’t feasible.

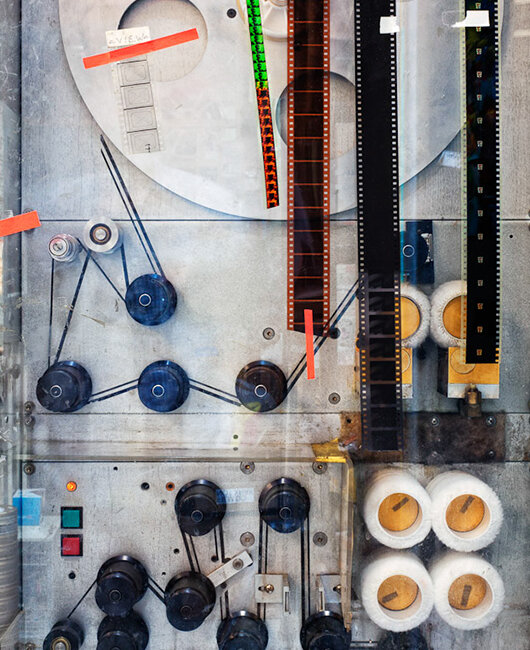

JR: This has been a filmmaking secret for a long time: if you want to make something look like it’s on film, you can shoot digital and then do a one-to-one transfer. Pablo Perez, who headed up all of our transfers, had done it a bunch of times before, so he already had a setup for it. Basically we ended up shooting digital on video formats — RED and Blackmagic — that could handle a high dynamic range where we weren’t going to lose the highlights the way video sometimes does. We took that video, did a grade on it to bring it into the right realm, as well as shifting the colors into the right area, and then we did the film transfers shot by shot. It was 2K footage, but he used a 4K monitor so there was no pixelation. And he shot it frame by frame using a mechanical setup with an old computer that ran a Bolex.AA: Kind of like old animation style.

JR: Yeah, so the monitor was where the animation would have been, and then the Bolex was rigged above it.

Was the look and type of film stock that you printed to determined by the archival you were trying to match?

JR: We’d often match whole sequences to the stock footage. The arrival at NASA sequence is a good example. That’s the most back-and-forth we did between archival and none. We started working in the additional grain early on in the previous scene. If you gradually start bringing it in, then you don’t notice the change once it clicks in.

AA: Our first line of defense in that matching process was our colorist, Conor Fisher. We’d give him the raw RED files, he’d do the first match to it, and then—

JR: Get it as close as possible. We noticed that when we went to film, it smoothed out everything. It took all of the slight differences, the curves, and the grain structure, and it painted a layer over the top that gave it a unified look.

Did you do anything with the printed film before going back to digital to make it look rougher?

Curt Lobb: Pablo would mess with the film reels; he’d dirty and scratch them up.

AA: There’s that interesting sequence with Bracket saying he’s going to shoot down Apollo 11. Matt [Johnson] buried that film because it’s the first thing his character buries in the movie.

CL: Was that the bucket of dirt in the shower?

JR: Yeah.

CL: I opened the shower one time and there was this big clump of dirt.

JR: It stayed there for a week. It was just a bucket of dirt.

Did it make a difference?

JR: Oh, yeah. You can see the moment where it kicks in.

That NASA arrival scene you mentioned was particularly impressive with regard to matching new stuff with stock footage. There were some great street shots with vintage cars that had to have been archival, but it cut so well with the Matt and Owen stuff — it was hard to tell where the archival ended and your movie began.

JR: Interesting story about that footage: it’s a little nod to Toronto. If you look at the mailboxes, they’re the wrong color for the States. That’s because it came from an amazing National Film Board of Canada (NFB) movie nobody’s seen, called Christopher’s Movie Matinee, which is this unbelievable documentary from 1968. A bunch of kids are trying to figure out how to make a movie for the NFB and what it should be about. Basically, NFB cameramen were hired to go with these teenagers and help tell the story of their life and what it’s like to be a kid in Toronto in the ’60s. It was right at the time when the Canadian government was deciding whether or not they were going to kick all the hippies out of Yorkville. It became very much about this divide between old and new.

These kids are similar to our film’s characters. They’re just guys messing around with a movie camera, which is why that footage of them goofing around in the street and waving to people fit so well in our film. Because filmmakers were so serious during that era, very little footage of that kind of jovial, loose camera stuff exists on 16mm.

AA: That’s why we gravitated toward the long-form documentary as a reference point, because it was clear that’s where people were spending the most time and felt more relaxed. In the Rolling Stones’ 1970 documentary Gimme Shelter, it’s clear those guys were with the band for so long. Or in the 12-hour documentary series An American Family, where filmmakers spent seven months with the Loud family, just living in their house. Things got kind of fun and weird.

JR: You’d have to search out the footage of filmmakers who were having fun and cameramen who weren’t paying that much attention or were distracted.

AA: And who were simply following something that was moving that they weren’t controlling. They weren’t keeping the movement going; they were just following it constantly.

You’ve done a couple of these found footage films where you have a dual role as the camera operator: using camera movement to emote, yet still capturing the action. Is doing this type of film second nature by now, or do you get specific direction?

JR: It’s sort of internalized at this point. You can feel it when you do a take that was a little too clean or you didn’t move right.

AA: You’re trying to capture interesting drama, as well as trying to react to being shot at.

CL: As far as matching new film to old stock footage from NASA, that’s what messed with us the most. All of that footage was shot on sticks, for the most part. Our movie is all shaky, and then we try to match it to this perfect stable shot of Mission Control. To try to get some kind of movement, we’d look through all of this old footage, and we’d look at the beginning and the end of takes when the cameraman wasn’t set up yet.

JR: He was just finding the shot.

Were those your favorite shots?

CL: Yeah, probably.

AA: Yeah, 100 percent.

JR: That’s where you really feel the people behind the camera too. In those moments, it’s like, “There’s something cool over there.” They pick up the camera and it’s shaky for a minute, but then it stabilizes.

Did you have to do anything to the cameras to help conceal that these images were being captured using modern gear?

AA: We used a lot of vintage lenses. We put old Bolex lenses on the Blackmagic.

JR: That was way more important than anything else. There are a couple of scenes where we couldn’t use the vintage lenses, and you can tell. It looks much more modern.

AA: We actually had a bunch of old Compact Prime lenses converted to PL. We originally had a Super 35 Angénieux lens, but it was way too big, too bulky. So we got these compact Angénieux lenses. They’re 40 years old, and we converted the back mount on them.

JR: We would have shot some scenes 4K, but the lenses wouldn’t let us.

AA: Some of the big VFX moments. But we really wanted it to be 2K too, because that’s the size of the 16mm frame.

So most of the color grading has to happen before you convert it to 16mm?

JR: Yeah, Conor did a full pass when it was still RED RAW. At that point, in terms of keying things out, if we wanted power window or track anything, it’s very hard to do once we go to 16, because they’re basically burning in all of this info. So he did a full pass before it went to 16, and that was crucial. It made a massive difference. He could push it quite far, and he could achieve film effects like a fading in the blacks that matched the older stocks.

Even though we were using a lot of older stocks, they would have been from the ’80s, not the ’60s. Film technology has improved to the point where film is much better now than it was in the ’60s, so we had to do some degrading early on in the first color pass. Shift some of the blacks a little toward red. Things that these ’60s films naturally do. Conor was huge for that.

Do you think it will ever be possible to achieve the full effect in digital without the 16mm intermediate?

JR: We tried. Honestly, I think if we could do it, then we would have done it. There’s something that happens — is it the uncertainty principle? It’s that thing you can’t predict. We could have given it to Conor, and he could have re-created exactly what happened in that shot from earlier in the movie. But those mistakes never happen twice — the way the colors shift in an unpredictable way, the way the highlights go a certain way.

AA: The way a hair would lie on the scan. You can’t design for that.

JR: You could intentionally do it, but you’d just be copying something you’d seen before. People are wired to pick apart images now. We spend all day looking at images and thinking about how they originated. We’ve developed a powerful vocabulary for seeing an image and knowing where it came from and who took it. That’s in our lexicon now through how much we learn by looking at images all day long. People are savvy to the point where they can subconsciously tell — whether they know it or not — if they’re looking at something from a certain era or a modern thing that’s trying to be that thing from a certain era.

Stranger Things is a great example of that. It has the look of an ’80s movie through and through, but you know it’s not an ’80s movie because you’re not watching it on film. Film does all these weird things that look like mistakes, but you can’t plan them. Through this process, we discovered that if you want something to look like it’s on film, the only way to get that look consistently is to actually use film.

In addition to being one of your shooting locations, the NASA archives turned out to be another invaluable resource for stock footage…

JR: That’s an amazing thing about NASA. Even to this day, all of their work, their photographs — except for the logo — become public domain the moment they take a photo. They want people to take their work and make art out of it. They would love it if people would make more art out of the Apollo photographs or the photographs they’re taking now. They want artists to do this, and I don’t think people know that. I hope one side benefit of us using their archives to make a farce about the moon landing being faked is that people will go, “Oh, there’s this huge database of beautiful photographs of incredible history that we can draw on to make other things.” NASA’s photo archive is accessible to everybody, and those photos are—

CL: Faked.

JR: Faked. [laughs] They were faked perfectly. Those were hand-painted by the best artists in America.

AA: If anybody ever had a question about the validity of the moon landing, they’d only have to tour the Johnson Space Center, and they’d instantly feel like there’s no way it didn’t happen. Matt has that great line in an interview, where he says, “If we didn’t believe in the moon landing, it would be a very different movie.”

CL: Then Jared said, “I think you can watch that movie on YouTube right now.”

Operation Avalanche opens in theaters on September 16.

Photos of Niagara Custom Lab were given courtesy of Michael Barker, from his photo series entitled “The Lab”. Production photos, in order of appearance, were given courtesy of Andrea Cuda, Colin Medley and Joey Shanks.