This guest article comes from our friend and sound designer Dallas Taylor. He’s worked as a sound designer for over 20 years, starting out at Fox, NBC, and Discovery, and then setting up his own company, Defacto Sound.

If you haven’t heard their name, you’ve probably heard their work for clients like Netflix, Nike, and Lexus. Perhaps even more than their sound design, what they’re best known for is Twenty Thousand Hertz—a lovingly crafted podcast about the world’s most recognizable and interesting sounds.

When you’re working on an edit, it’s easy to focus all your energy on the visuals: the shot selection, the cuts, and the transitions.

It makes sense. After all, the film is, first and foremost, a visual medium.

But having said that, it’s crucial to also think about how sound will fit into your edit. And not just the music, but the actual sound design.

Good sound design can make or break an edit. Nail it, and each scene will feel rich and full of life.

Luckily, there are some simple things you can do to make sure you’re always editing with sound design in mind.

Along the way, I’ve assembled a great team. And I thought for this blog it would make sense to speak to one of our sound designers, Jai Berger, to get his perspective.

The first thing I asked Jai was this:

At what point should you actually bring the sound designer into the project?

“We love it when editors reach out early to brainstorm ideas,” answers Jai. “That way, a project can be set up for success before anything gets fully locked in place.”

This is exactly what happened with the project I’ll be using as a case study: our sound design for the Corvette Z06 documentary.

For this, we designed several vignettes. They’re all about excitement and energy, so the edit and the sound design had to reflect that. In this blog post, I’m going to refer specifically to this vignette.

The filmmakers at Porch House brought us in once they had a rough edit in place. We then picked out a few moments where we saw opportunities for great sound design, and they made minor adjustments so those would work. For example, the moment at 0:05 seconds where the music is timed to the tail lights turning on. We suggested adding in the sound of the car’s ignition, and they made the visual adjustments so there would be space for this to happen.

This is a pretty common issue: the edit already looks great, but it needs a bit more space for the sound design to work. As Jai explains: “Visual ideas come across quicker than sonic ones. So, a 15-frame shot of a beach could be enough time for someone to take in the visual details. However, that’s not enough time to include all of the sonic details.”

One way of making sure sound design has enough space to work is by asking for a sound design mockup before you begin your edit. That’s where the sound designer comes up with a sound concept without any visuals. This is something we did for Nike’s Kawhi campaign, which you can see here.

“By building out multiple versions of the soundtrack, we gave the editors an idea of the vibe before it was even shot,” explains Jai. “The debate dialogue had a natural increase in emotion and energy throughout, so we wanted to create our own version of a ‘music track’ that helped emphasize that arc.”

Another advantage of this approach is that it gives you a place to start your edit from. Plus, if you’re not sure what you want from the sound design, it gives you a chance to hear some options.

However, if you already have an edit in place, there are still plenty of opportunities for sound design to heighten the emotion of a scene.

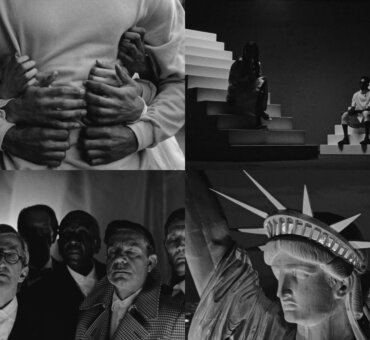

“The opening montage from the Corvette vignette is a good example of this,” says Jai. “It already looked great, but we helped tie a number of intense close-up shots in the first three seconds together through cinematic sound design. It’s a combination of real car sounds, synths and other sounds. This then crescendos until we have the release with the wide vista shot, where we let the previous sounds fade out with a touch of reverb.

“We often think about sound design in these terms, with peaks as the energy increases, and then valleys where it is released.”

In fact, you can see this approach throughout the Corvette film. But again, the sound design needs to have some space in order to be effective.

“You have to let these moments breathe,” Jai confirms. “Some shots may feel too long without sound design, but once you add that in, you’ll notice a big difference, and a shot that felt too long suddenly feels just right.”